Interview with Nicolas Rakotopare

“Photography complemented my work by enabling me to not only collect data but beautiful images that can be used to convey that data in a different way.”

We stumbled upon Nicolas’ work one day when a mesmerising photo of a female Leopard in the Yala National Park in Sri Lanka appeared on our Instagram feed. We were instantly hooked. Since then, we have closely followed his captivating wildlife photography and the trips this intrepid conservation biologist has embarked upon to some of the world’s most remote places. Born on the island of Madagascar but now residing on the Gold Coast, he travels the planet to document some of our world’s most magnificent ecosystems. Despite limited internet access due to Nico being submerged in the middle of the jungle, we were able to ask him all about his work, his passion and his journeys into the wild to not only study the species around him but to reconnect people with nature.

A critically endangered Indri from Madagascar, one of the largest lemurs in the world.

© Nicolas Rakotopare

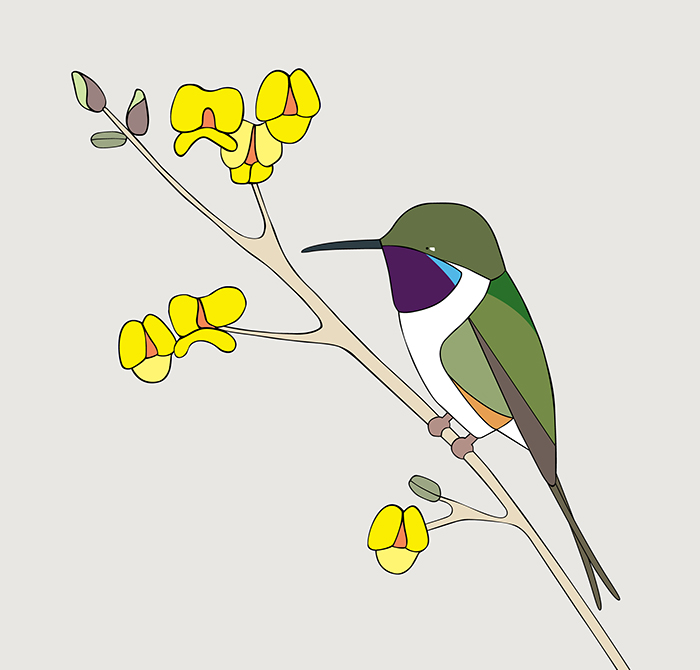

Tell us about your journey as a conservation biologist. How has photography complemented your work in this field?

I chose to major in Conservation Biology because of the broad scope of work it comprises. I like to see and approach things from a holistic point of view. Conservation Biology deals with many aspects of nature from Zoology to Social sciences and geography for example. I like that a lot of conservation biology topics can be approached from a multidisciplinary point of view.

A lot of biologists will carry a camera to document their research and I am no exception but I guess I push it a bit further by actively seeking more photos outside of the scope of my field work. Photography complemented my work by enabling me to not only collect data but beautiful images that can be used to convey that data in a different way. Sometimes straight data can alienate people from the work but seeing a photograph of the study area or a particular species can really help people connect with the work.

Jade Tree Frog found in Borneo.

© Nicolas Rakotopare

What is the purpose of your photographic records?

Some images are for my personal records but I mainly use the images combined with compelling stories to connect people with nature. I do some field biology tutoring and wildlife photography is a great medium to get them motivated. Sometimes it’s a way for me to get them to discover their own backyard, when I tutor in Australia many students have never heard of some of their own backyard species and I show them photographs and field stories to get them interested. Wildlife images work on so many levels, inspiration, conservation and education!

Black Heron in Lake Tsarasaotra, Madagascar.

© Nicolas Rakotopare

We love your Instagram feed @lerako and stories. When did you decide to travel and how has this changed how you view the natural world?

Travelling hasn’t really changed my view of the natural world if anything it’s the other way around. In the past, travel was mostly a necessity to see family and friends who are scattered around the world. Since studying conservation biology and focusing my photography on nature and wildlife, I now travel to see the natural world and be amazed by it. I embarked on a long journey about 17 months ago, a mix between research and photography. I wanted to see the world but not be confined on the main tourist path. It’s not always possible to get out of it but by taking part in research in several places I got to see off the beaten trail parts of the countries I visited. Every single destination I have travelled to in the past year was for the purpose of seeing wildlife, ecosystems or wild places that I always wanted to see and photograph.

Bornean Keeled Pit Viper.

© Nicolas Rakotopare

You grew up in Madagascar and recently embarked on a trip to revisit the country. How has the landscape changed and how important is it to tackle poverty in order to protect the island’s endemic biodiversity?

It was my first trip back with my “biologist eyes”, I had not been in the country for 12 years! I can’t really say I see a difference in the landscape from personal experience but my training as a biologist and everything I read and studied came to life when cruising on the Malagasy roads and all you can see is erosion, burnt landscape, Australian eucalyptus and acacias planted to try and hold the soil and make more firewood… It takes a while when you drive from the capital to the east coast before you can see any sort of native vegetation. Poverty is probably the number one problem to tackle before the endemic species of Madagascar stand a real chance. Poverty drives a lot of the pressure on the wildlife, directly and indirectly via habitat destruction, poaching and corruption.

Eulemur fulvus in the rainforest, Madagascar.

© Nicolas Rakotopare

What do you see as the future for conservation?

More people caring. People from all walks of life understanding the importance of and caring about our natural world. I think that is were some of the future for conservation lies. People really need to reconnect with nature and wildlife, not only from their TV sets and phones, watching documentaries but also to get out and travel to feel and experience for themselves. I feel this will give them a better understanding as to what conservation is, what it stands for and how important it is.

Female leopard, Yala National Park, Sri Lanka.

© Nicolas Rakotopare

What kind of equipment do you use now, and what did you start with?

In high school I was using a Nikon bridge camera, mainly to photograph my friends surfing but when I look back in these folders there is always photos of wildlife somewhere, some birds I saw or chameleons in the schoolyard! Later I got a second hand Canon EOS 350D and a 50mm 1.8 lens. This is when I really started to learn about manual settings, light, etc… Nearly a decade later I’ve used many lenses and bodies but always stuck to Canon. My main work horse is a 7DmkII combined with a 300mm f/2.8 IS USM Canon lens and a 100mm macro. I’ve lost a lot of gear to the harshness of the months in tropical regions in the past year, humidity, rust, fungus…

A stork-billed kingfisher in the Kinabatangan Wildlife Sanctuary, Borneo.

© Nicolas Rakotopare

What is the one piece of advice that you would give to other up and coming nature photographers?

Don’t forget to charge your camera and empty your memory cards before you head out! Joke aside one of the advice I have heard many times and I tend to use myself it to “shoot things that you want to be hired to shoot” so that when the opportunity comes around to be doing it professionally you will have experience in this area.

Nicolas back in 2011 during his first trip to Nepal.

© Nicolas Rakotopare

Follow Nicolas’ travels and view his compelling photographs on his website lerako.net and his instagram @lerako

Sorry, the comment form is closed at this time.